Functional play is critical for children’s development, especially for autistic children who may struggle with using toys as intended. Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) techniques provide a structured way to teach these skills by breaking down play activities into smaller steps, using reinforcement, and tailoring support to individual needs. Here’s what you need to know:

- What is Functional Play? It involves using toys correctly, like rolling a car or stacking blocks, and is essential for cognitive, social, and language development.

- Why ABA Works: ABA methods like Discrete Trial Teaching (DTT), task analysis, and chaining help children learn play skills step-by-step.

- Key Techniques:

- DTT: Uses simple instructions, immediate feedback, and rewards.

- Chaining: Breaks activities into steps taught sequentially.

- Reinforcement and Prompting: Encourages correct actions with praise or rewards, gradually reducing assistance.

- Stages of Play Development: ABA supports progress from functional play to symbolic play (imaginative use) and cooperative play (social interactions with peers).

- Practical Tips for Parents: Create structured play environments, use visual aids, and track progress with tools like apps to monitor skill development and generalization.

How to Teach Play Skills Using ABA When a Child Has No Play Skills

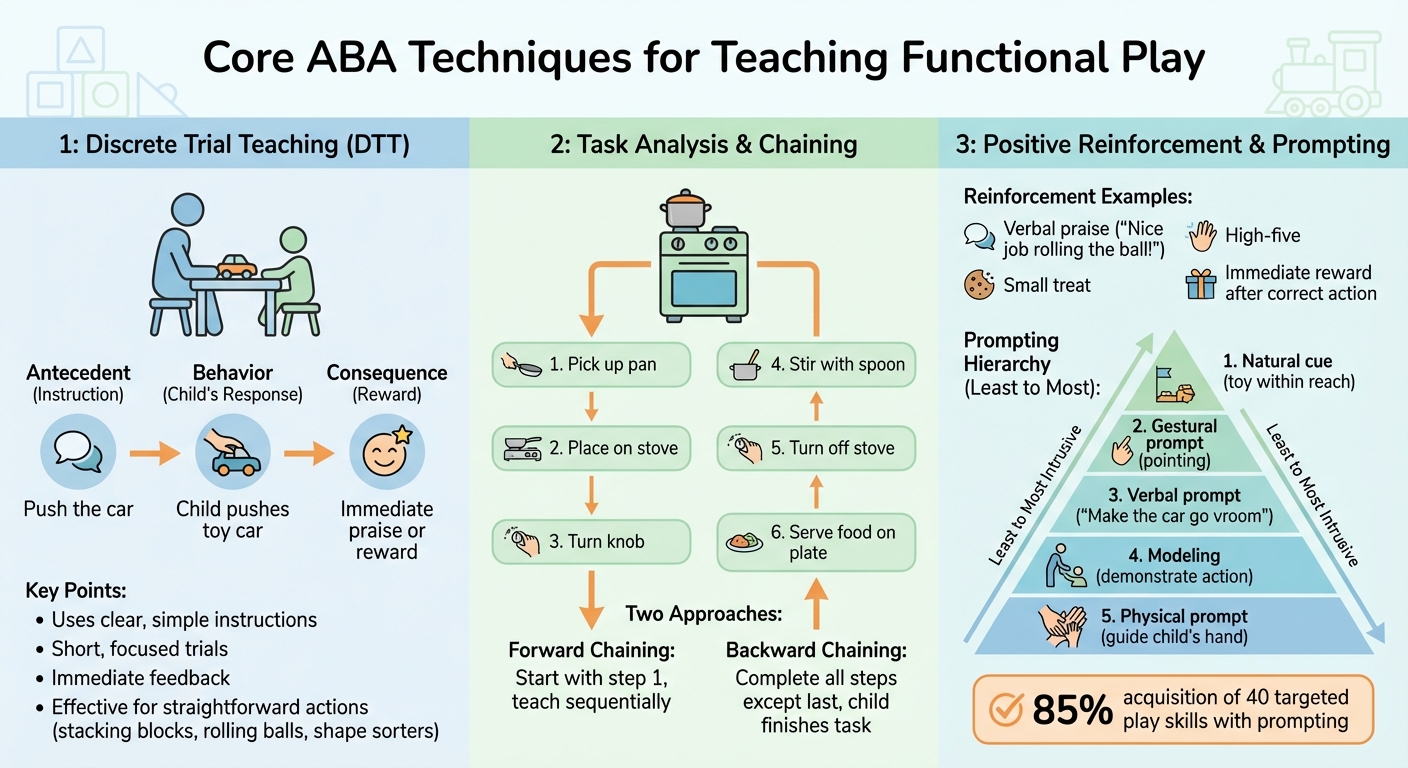

Core ABA Techniques for Teaching Functional Play

Core ABA Techniques for Teaching Functional Play Skills

Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) therapy uses a range of techniques to help children build functional play skills. These methods focus on breaking down complex activities into smaller, manageable steps and providing support tailored to the child’s needs. They’re practical and can easily be applied at home. Let’s explore some key ABA strategies for teaching functional play.

Discrete Trial Teaching (DTT)

DTT is a structured, step-by-step teaching approach that follows a simple three-part sequence: Antecedent (the instruction), Behavior (the child’s response), and Consequence (the feedback or reward). For instance, you might say, "Push the car" (antecedent), your child pushes the toy car (behavior), and you immediately offer praise or another reward (consequence).

This method is particularly effective for teaching straightforward play actions, like stacking blocks, rolling a ball, or placing shapes into a sorter. The key is to use clear, simple instructions, such as "Feed the baby", and to keep each trial short and focused. By immediately rewarding the correct behavior, your child learns which action earned the praise, making it more likely they’ll repeat that action in the future.

Beyond DTT, other strategies focus on teaching play as a series of sequential steps.

Task Analysis and Chaining

Task analysis involves breaking down an entire play activity into smaller, individual steps. For example, teaching a child to play with a toy kitchen might involve steps like picking up a pan, placing it on the stove, turning the knob, stirring with a spoon, turning off the stove, and serving food on a plate. Writing out these steps helps create a clear teaching plan.

Once the steps are outlined, chaining is used to teach them in order. With forward chaining, you start with the first step – helping your child pick up the pan – and then gradually teach the remaining steps. Backward chaining, on the other hand, works in reverse: you complete all the steps except the last one, allowing your child to finish the task independently. This approach can boost confidence, as the child experiences immediate success and the satisfaction of completing the activity.

Positive Reinforcement and Prompting

Positive reinforcement makes learning engaging by rewarding the desired behavior as soon as it happens. For example, if your child uses a toy correctly, you can respond with verbal praise ("Nice job rolling the ball!"), a high-five, or even a small treat. The immediate reward helps your child connect their action to the positive outcome.

Prompting is another key tool to guide your child toward success. It involves using a hierarchy of prompts, starting with the least intrusive and moving to more direct assistance as needed. For instance:

- Begin with a natural cue (placing the toy within reach).

- Move to a gestural prompt (pointing at the toy).

- Add a verbal prompt ("Make the car go vroom").

- Use modeling (demonstrating the action yourself).

- Finally, apply a physical prompt (gently guiding your child’s hand).

The goal is to start with minimal help and gradually reduce the level of prompting as your child gains confidence and independence. Research shows that using prompting within direct instruction can lead to significant progress, with participants acquiring an average of 85% of 40 targeted play skills [7].

Stages of Play Development in ABA Therapy

Play skills don’t emerge all at once – they grow step by step, building on one another over time. ABA therapy recognizes this natural progression and uses specific strategies to guide children from simple toy use to more advanced social play. By understanding these stages, you can better support your child’s development and help them navigate through each phase.

Functional Play: Using Toys as Intended

Functional play is where it all begins. It’s about using toys the way they’re designed – rolling a toy car, stacking blocks, or pretending to stir soup with a toy spoon [4].

For children with autism, repetitive behaviors like spinning wheels or lining up toys often take the place of functional play [4][5]. ABA therapy addresses this by modeling appropriate toy use, prompting the child to imitate, and rewarding successful attempts. For example, one study showed that when preschoolers used a photographic activity schedule, they started engaging independently in functional playground activities [3]. However, when the visual supports were removed, their play levels dropped, only to improve again when the supports were reintroduced.

The goal here is consistency. Once a child can use toys as intended without help, they’re ready to move on to more imaginative types of play.

Symbolic and Pretend Play

Symbolic play takes functional play to the next level by adding imagination. Instead of just pushing a toy car, a child might pretend the car is driving to the store. Or they might use a block as a pretend telephone. This type of play usually starts to develop between 18 and 24 months [4], but children with autism often need extra guidance to make this leap.

ABA therapy helps through a method called "Join, Imitate, Expand." A therapist first joins the child in their activity, then imitates what they’re doing, and finally adds an imaginative element – for example, turning block stacking into building a "house" for toy animals [2]. Visual aids like play scripts can also be helpful. For instance, a script for "playing doctor" might include pictures showing steps like checking a doll’s heartbeat, giving medicine, and applying a bandage.

Another effective tool is Video Self-Modeling, where children watch videos of themselves performing play actions. In one study, a 5-year-old with autism watched edited videos of themselves engaging in play. Not only did their functional play improve, but they also began applying these skills to other toys, with the progress lasting for one to two weeks after the intervention [2].

Symbolic play sets the stage for the next level: cooperative play, where social interaction takes center stage.

Cooperative Play with Peers

Once children have mastered individual play skills, they’re ready for cooperative play. This stage involves working with others toward a shared goal – whether it’s building a fort, taking turns in a board game, or playing "restaurant" with assigned roles. Cooperative play requires advanced social skills like sharing, turn-taking, and following rules [8].

For children with autism, this can be especially challenging. Studies show they spend about 70% less time engaged in functional play compared to their peers [6]. To bridge this gap, ABA therapy often uses peer-mediated interventions, where neurotypical peers are taught to initiate and sustain social interactions. Social stories and visual schedules can also help explain the steps of social play, while prompts guide children until they can manage on their own.

A 2019 meta-analysis revealed that 89% of participants showed significant improvements in functional play skills after ABA interventions [6]. Structured playdates with supportive peers, visual schedules (e.g., "First we build, then we share, then we clean up"), and immediate positive reinforcement for successful interactions all play a role in helping children thrive at this stage.

sbb-itb-d549f5b

Practical Strategies for Parents and Caregivers

ABA therapy doesn’t end when the session wraps up – it extends into everyday life at home. What happens between appointments plays a key role in your child’s progress. The great news? You don’t need a degree in behavioral science to support your child’s functional play skills. With some thoughtful preparation, regular observation, and simple tracking techniques, you can create a home environment that encourages daily growth. These strategies align seamlessly with the ABA methods introduced during therapy sessions.

Setting Up a Home Environment for Play

Creating an organized and focused play space can make a big difference. Start by limiting the number of toys available at any one time. Too many options can overwhelm your child and make it harder for them to focus [9]. Instead, choose a few toys your child enjoys or is currently learning to use.

Using visual boundaries can help your child understand where play happens. A play mat, tape on the floor, or a specific corner of a room clearly marked as the "play zone" can provide structure and reduce distractions [4]. This kind of setup helps your child stay engaged with the activity in front of them.

You might also consider using “play bins.” These are containers or bags, each holding a single activity that your child has mastered. For example:

- One bin could include a toy car and a ramp.

- Another might have stacking cups.

- A third could contain a shape sorter.

Your child can work through one bin at a time, moving to the next after completing an activity. A preferred reward can be offered once all bins are finished, encouraging both focus and independence [10].

Visual schedules are another effective tool. Simple picture cards or written lists can outline upcoming activities, giving your child a clear idea of what’s next. A 2016 study by Akers et al. demonstrated the power of visual schedules. Preschool children (ages 4–5) used activity pictures to organize their playground time. After completing tasks like sliding or climbing, they earned a preferred edible reward. When the visual schedules were removed, their independent engagement declined – a clear sign of how important these supports are for maintaining progress [3].

By tailoring your home environment in these ways, you give your child the tools they need to build functional play skills outside of therapy sessions.

Using Reinforcement and Observation

Reinforcement is more than just handing out rewards – it’s about identifying what truly motivates your child in the moment. As Mary Staub, M.Ed., BCBA, LBA, explains:

"Something is only a reinforcer if it increases the target behavior" [10].

If stickers aren’t motivating your child today, offering them won’t encourage engagement. Pay attention to what excites or interests your child and use that as a reward.

Differential reinforcement can also encourage independence. Offer higher-value rewards, like a favorite snack, when your child completes a play action without help. For actions that require prompting, provide lower-value rewards, such as verbal praise [6]. This approach naturally motivates your child to try tasks on their own.

You can also use the "Join, Imitate, Expand" strategy, which involves joining your child’s play, imitating their actions, and gradually introducing new behaviors [2]. While playing together, narrate their actions with simple, descriptive statements. For instance, say, “You’re stacking the red block on top,” or “The car is rolling fast!” This not only exposes your child to language but also helps them connect words to their actions [2].

Tracking your child’s progress is equally important. Pay attention to metrics like:

- How often they complete actions independently (e.g., rolling a car without help).

- How long they stay focused on a toy.

- The variety of toys they engage with [9][6].

By observing and recording these details, you can fine-tune your approach and recognize when your child is ready to take on new challenges.

Documenting Progress with Tools Like Guiding Growth

Consistent documentation transforms observations into valuable insights. By tracking your child’s play behaviors systematically, you can see what’s working, notice patterns, and share useful information with your child’s therapy team. Accurate records also help adjust ABA interventions to better meet your child’s needs.

For example, tracking how often and how long your child engages with toys can quickly highlight progress or areas needing attention [9][6]. This might include frequency counts (how often a behavior occurs), duration (time spent on an activity), and whether certain behaviors happen at specific times.

That’s where an app like Guiding Growth comes in handy. It allows you to log your child’s daily play activities, behaviors, and developmental milestones in one central place. Instead of juggling paper logs or scattered notes, you can record observations in real-time. The app then converts this data into visual patterns, making it easier to spot progress – like your child gradually spending more time with building blocks or consistently using toys as intended without prompts.

When meeting with your child’s therapist or healthcare provider, Guiding Growth can generate detailed reports. These reports highlight emerging skills, preferred activities, and areas needing extra support. Sharing this information empowers professionals to make informed decisions about adjusting therapy goals.

The app also helps track whether your child is generalizing skills – using play behaviors across different settings (like the living room versus the bedroom), with various people (you versus a sibling), or with different toys [6]. Generalization is key because a skill isn’t fully mastered until it can be applied flexibly in everyday situations.

Monitoring Progress and Adjusting ABA Interventions

Tracking progress is a cornerstone of effective ABA interventions. Tools like Guiding Growth make it easier to document milestones, but consistent evaluation is key. Progress isn’t always linear; it can vary from week to week. By regularly reviewing what’s working and what isn’t, you can make informed decisions about when to advance or tweak your approach.

Assessing Skill Acquisition

Measuring progress requires objective data to determine whether your child is genuinely mastering functional play skills. Therapists often rely on standardized tools like the Verbal Behavior Milestones Assessment and Placement Program (VB-MAPP) or the Assessment of Basic Language and Learning Skills (ABLLS-R) to establish baselines and track development over time [6].

However, informal observations are just as valuable. Watching your child during free play at home, noting how they interact with toys, and discussing their behavior with other caregivers can provide meaningful insights. Therapists typically classify responses into three categories:

- Independent responding: The child completes the action without assistance.

- Successful responding: The action is completed with a prompt.

- Unsuccessful responding: The child either refuses or performs the action incorrectly.

Tracking these responses over time helps identify patterns, such as whether your child is moving toward independence or becoming overly reliant on prompts.

To make progress measurable, align your goals with the SMART framework – Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound. For instance, instead of a vague objective like “improve play skills,” a SMART goal might be: “Within three months, my child will independently use three different toy vehicles for five minutes daily.” This approach provides clear metrics to evaluate success. Research from UCLA even shows that children receiving intensive ABA services exhibit a 250% increase in functional play behaviors compared to control groups [6].

Here are some metrics you can track:

| Metric to Track | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency | How often a specific play action occurs | Number of times a child rolls a car in 10 minutes |

| Duration | How long the child engages with a toy | Minutes spent "cooking" in a toy kitchen |

| Independence | Percentage of independent actions | Completing a 5-piece puzzle without help |

| Generalization | Using skills in different contexts | Playing with a toy phone at home after learning it in therapy |

Generalization is especially important. Skills learned in one setting should transfer to others – whether it’s using a toy phone at home after practicing in therapy or playing with different caregivers. If you’re using an app like Guiding Growth to log activities, you already have a head start. Data like frequency counts, engagement duration, and notes on independence can help identify trends. For example, you might notice certain toys consistently hold your child’s attention or that they engage more successfully at specific times of day. This information can guide adjustments to therapy strategies.

When to Adjust Play Interventions

Every intervention needs to evolve over time. Children grow, their interests shift, and what worked last month might not resonate today. Recognizing when and how to adjust is just as crucial as implementing the initial plan.

If progress stalls, consider breaking tasks into smaller steps or transitioning from Discrete Trial Training (DTT) to Natural Environment Teaching (NET).

"By continuously tailoring support based on observed outcomes, caregivers and therapists can create a responsive learning environment that fosters the child’s developmental journey." – Step Ahead ABA [11]

Sometimes, stereotypy – repetitive behaviors – can interfere with functional play. In such cases, strategies like Functional Communication Training or modifying the environment can help. For instance, allowing brief engagement in the stereotypic behavior before a session (known as an "abolishing operation") can reduce its appeal during structured play.

Motivation is another critical factor. If your child seems disengaged or avoids certain toys, it might be time for a new preference assessment. Research from All Points ABA highlights:

"When activities align with a child’s preferences, motivation naturally increases, leading to better participation and sustained attention during sessions." – All Points ABA [1]

Prompt dependency, where a child relies heavily on assistance, is another common challenge. To address this, implement a stricter prompting hierarchy or try time-delay procedures, giving your child more time to initiate tasks independently.

Behavioral challenges like frustration, meltdowns, or avoidance during play sessions can signal that the current approach is too difficult or that the reinforcement isn’t effective anymore. Regular data collection can help pinpoint these issues. If a goal isn’t met within the expected timeframe (usually three months), it’s a clear sign to reassess and modify the intervention.

| Sign for Adjustment | Potential Modification |

|---|---|

| Skill Plateau | Break tasks into smaller steps or switch teaching methods (e.g., DTT to NET) |

| Prompt Dependency | Use a stricter prompting hierarchy or time-delay procedures |

| Decreased Motivation | Conduct a new preference assessment or incorporate current interests |

| Interfering Stereotypy | Implement Functional Communication Training or modify the environment |

| Generalization Issues | Practice skills in multiple settings and with different partners |

Conclusion

Teaching functional play through ABA techniques creates opportunities for connection, learning, and joy. The methods shared in this guide, from Discrete Trial Training to Natural Environment Teaching, provide a structured way to help children with autism build play skills that support their social and cognitive growth.

Simple, everyday moments – like following your child’s lead during snack time, narrating their actions during bath time, or using visual aids during outdoor play – can naturally reinforce therapy goals. As the NeuroLaunch Editorial Team explains:

"By focusing on functional play skills, we’re not just teaching children how to play – we’re opening doors to a world of learning, connection, and joy" [4].

These everyday practices ensure that skills translate across different environments and interactions, making them truly meaningful.

Tracking progress is an essential part of this process. Tools like Guiding Growth help turn your observations into actionable insights by measuring aspects like play frequency and duration. This data not only informs decisions but also supports productive conversations with therapists and healthcare providers, ensuring ABA strategies continue to evolve alongside your child’s needs.

It’s important to remember that progress isn’t always a straight line. There will be weeks of noticeable improvement and others where things may seem to plateau. Consistency is key – celebrate small victories and adjust your approach based on what the data shows. Whether it’s breaking a complex play activity into smaller steps or weaving your child’s favorite interests, like trains, into play sessions, every effort helps to strengthen functional play skills.

Start with one strategy from this guide – like the Join, Imitate, Expand framework or setting up a structured routine – and focus on it for the next week. Observe, adapt, and document as you go. Building play skills is a gradual process, but each step forward is meaningful progress.

FAQs

How can I use ABA techniques to teach my child functional play at home?

Teaching functional play at home using ABA techniques can be a rewarding way to support your child’s development. Start by showing them how to engage in the activity you’re teaching. For instance, if you’re working on stacking blocks, demonstrate the process step by step. Then, gently guide your child to copy the action, offering help as needed. Over time, you can gradually step back and let them take the lead.

Break the activity into smaller, easy-to-follow steps. This makes it less overwhelming and allows your child to focus on mastering one part at a time. Celebrate even the smallest achievements with immediate positive feedback, like a cheerful “Great job!” or a small treat. This kind of encouragement motivates them to keep trying. You can also weave play into everyday tasks, like sorting laundry or setting the table, to make learning feel like a natural part of their day.

The most important part? Stick with it. Regular practice not only helps your child develop stronger play skills but also boosts their confidence and fosters a sense of independence.

What’s the difference between forward chaining and backward chaining when teaching play skills?

Forward chaining and backward chaining are two techniques used to teach play skills, differing mainly in the sequence in which steps are introduced and practiced.

With forward chaining, the focus is on teaching the first step of a task first. Once the child masters that step, the next one is introduced, and so on, until they can complete the entire activity without help. This approach emphasizes building independence in starting tasks.

On the other hand, backward chaining begins with the last step of the task. The child is guided through the earlier steps, but they independently complete the final step. This method can be particularly motivating because the child immediately experiences the satisfaction of completing the activity.

Both strategies are effective, and the choice between them depends on the child’s individual needs and the specific skill being taught.

How can I help my child use play skills learned in therapy in everyday situations?

To help your child use play skills in everyday life, try practicing these skills in various environments – whether at home, school, or out and about. This approach helps them adjust their play behaviors to different settings and interact with different people.

Incorporate tools like visual supports, such as activity schedules or visual cues, to set clear expectations and make transitions easier. You can also weave play into daily routines – like cooking together, bath time, or a trip to the park – making the learning process feel more natural and engaging. Using consistent prompts and reinforcement across these settings can further strengthen their ability to apply these skills in different situations.

With regular practice, consistency, and exposure to diverse settings and individuals, your child will gain confidence in using their play skills across a variety of real-life scenarios.